By Marvin Hokstam

AMSTERDAM — On August 28 it will be exactly 500 years ago that one of history’s most tragic and significant events started to unfold, new research has indicated. A tragic event that caused unimaginable suffering and even today leaves a legacy of poverty, racism, inequality and elite wealth across four continents. But it also quite literally changed the world and still geopolitically, socially, economically and culturally continues to shape it.

“Almost completely ignored by the modern world, this month marks the 500th anniversary of the birth of the Africa to America transatlantic slave trade. New discoveries are now revealing the details of the trade’s first horrific voyages,” the Independent wrote last week in an extensive report on new, yet unpublished research by two American professors, Dr David Wheat, of Michigan State, and Dr Marc Eagle, of Western Kentucky University.

“There has been a general failure by most historians and others to fully appreciate the huge significance of August 1518 in the story of the transatlantic slave trade”

Arguim

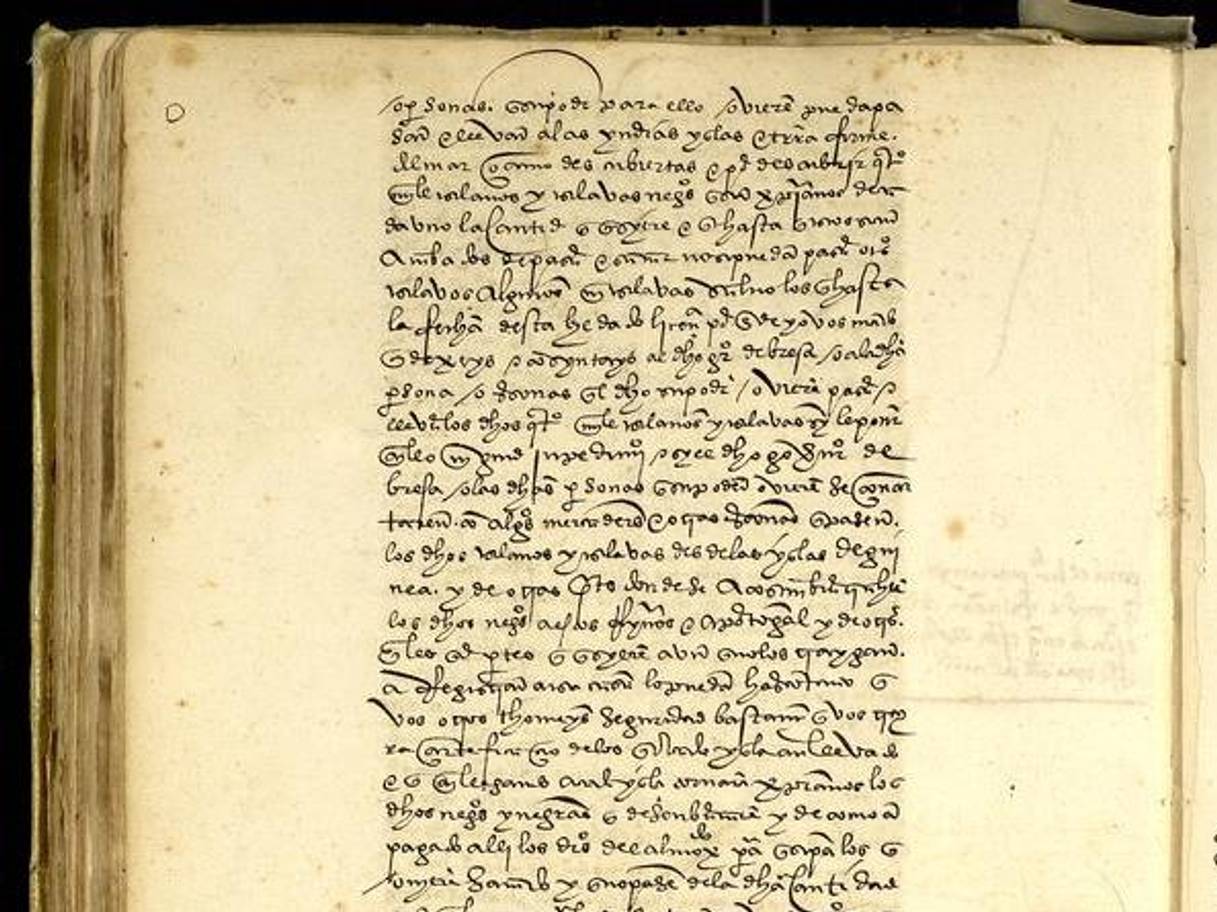

The research is premised on the charter the King of Spain, Charles I, issued on 28 August 1518, authorising the transportation of abducted black people direct from Africa to the Americas. Up until that point Africans had usually been transported to Spain or Portugal and had then been transshipped to the Caribbean.

The research is premised on the charter the King of Spain, Charles I, issued on 28 August 1518, authorising the transportation of abducted black people direct from Africa to the Americas. Up until that point Africans had usually been transported to Spain or Portugal and had then been transshipped to the Caribbean.

In the charter, the Spanish king gave one of his top council of state members, Lorenzo de Gorrevod, permission to transport “four thousand negro slaves both male and female” to “the [West] Indies, the [Caribbean] islands and the [American] mainland of the [Atlantic] ocean sea, already discovered or to be discovered”, by ship “direct from the [West African] isles of Guinea and other regions from which they are wont to bring the said negros”. Although the charter has been known to historians for at least the past 100 years, nobody until recently knew whether the authorised voyages had ever taken place.

The research shows that they did, in 1519, 1520, May 1521 and October 1521. These four voyages (all discovered in Spanish archives by the American historians over the past three years) were from a Portuguese trading station called Arguim (a tiny island off the coast of what is now northern Mauritania) to Puerto Rico in the Caribbean. The first three carried at least 60, 54 and 79 slaves respectively – but it is likely that there were other voyages from Arguim to Hispaniola (modern Haiti and Dominican Republic).

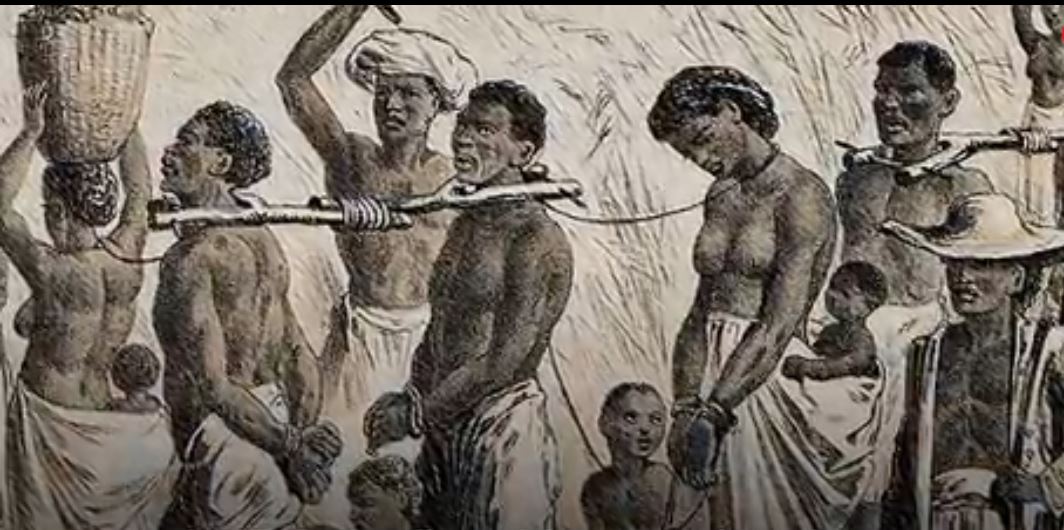

The trade was a catastrophe for Africa. The Arab slave trade had already had a terrible impact on the continent – but European demand for cheap labour in the new regions they were colonising worsened the situation substantially. The European slave traders massively expanded demand – and consequently, in the end, triggered a whole series of terrible intra-African tribal wars.

The issuing of the royal charter 500 years ago not only led to the kidnapping of millions of people and a lifetime of subjugation and pain for them, but also led to the political and military destabilization of large swathes of an entire continent.

LINKED

But this African catastrophe was linked to another terrible human disaster on the American side of the Atlantic, the sheer scale of which is only now being revealed by archaeology. For the main reason that the Europeans needed African workforces to be shipped to the Caribbean was because the early Spanish colonisation of that region had led to the deaths of up to 3 million indigenous Caribbean people, many of whom the Spanish had already de facto enslaved and had intended to be their local workforce.

When Columbus reached Hispaniola in 1492, the island probably had a population of at least 2 million. By 1517, this had been reduced by at least 80 per cent – due to European-introduced epidemics, warfare, massacres, starvation and executions.

The reality was that, by 1514, according to a government census, there were only 26,000 indigenous people left under Spanish control – and the Spanish feared that number would further reduce. It was this population collapse and the fear that it would continue that appears to have forced the Spanish king to, for the first time, authorise direct slave shipments from Africa to the Americas. Spain was desperate to ensure that its royal goldmines and agricultural estates in Hispaniola and its economic projects on the other Caribbean islands would not founder for lack of manpower.

Indeed, just a few months after Charles had issued his 1518 slave trade charter, around two-thirds of all the remaining original inhabitants of Hispaniola and Puerto Rico perished in the New World’s very first smallpox epidemic.

IGNORED

But, apart from the Spanish king himself, who were the people who launched the direct transatlantic slave trade from Africa to the Caribbean exactly 500 years ago? The most senior was Laurent de Gouvenot, the Flemish aristocrat and member of the Spanish king’s council of state, who Carlos awarded the slave trade charter to. But Laurent did not actually do the appalling dirty work himself.

But, apart from the Spanish king himself, who were the people who launched the direct transatlantic slave trade from Africa to the Caribbean exactly 500 years ago? The most senior was Laurent de Gouvenot, the Flemish aristocrat and member of the Spanish king’s council of state, who Carlos awarded the slave trade charter to. But Laurent did not actually do the appalling dirty work himself.

As he was specifically allowed to by the charter, he subcontracted the operations to Juan Lopez de Recalde, the treasurer of the Spanish government agency with responsibility for all Caribbean matters, who in turn sold the rights to transport 3,000 of the 4,000 Africans to merchant Agostin de Vivaldi and his colleague Fernando Vazquez, and the right to carry the remaining thousand Africans to merchant Domingo de Fornari.

All these businessmen had substantial mercantile experience and Fornari came from a slave-trading family with a long experience of human trafficking in the Eastern Mediterranean.

It was a profitable start of the centuries’ long disaster. Over the subsequent 350 years, at least 10.7 million black Africans were transported between the two continents. A further 1.8 million died en route. Carlos’ decision to create a direct Africa to America slave trade fundamentally changed the nature and scale of this terrible human trafficking industry.

The historians say that the year 1518 is therefore one of the most significant dates in the whole of human history. The call it significant factor, the way in which Spain and Portugal have had relatively little interest in their crucial roles in the history of the transatlantic slave trade. “There has been a general failure by most historians and others to fully appreciate the huge significance of August 1518 in the story of the transatlantic slave trade,” said one of Britain’s leading slavery historians, Professor David Richardson of the University of Hull’s Wilberforce Institute for the Study of Slavery and Emancipation.

This story appeared in The Daily Herald, Saturday August 25, 2018